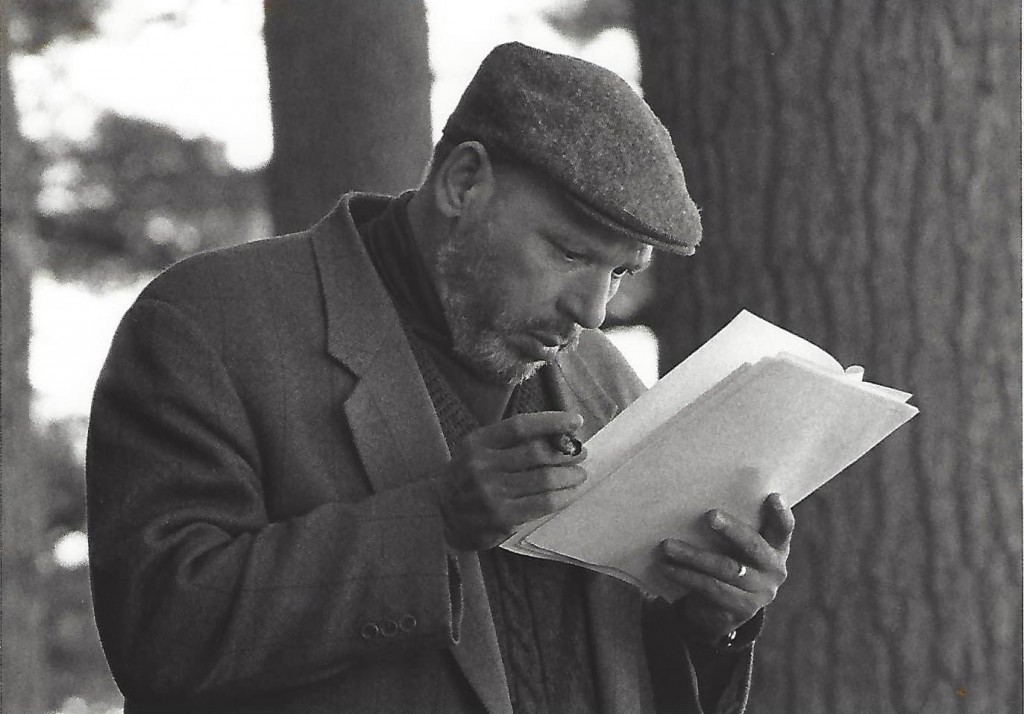

Baltimore Theatres Go All In on August Wilson

Over the next 3 years at 10 Charm City venues, the playwright’s entire American Century Cycle will unfold in chronological order.

By Daniella Ignacio

Originally published in American Theatre on September 3, 2024

August Wilson’s plays reflect survival, resilience, and change among Black Americans throughout the 20th century. With the Baltimore August Wilson Celebration, in which all 10 plays of Wilson’s American Century Cycle will unfurl in order over three years, Baltimore theatres are showcasing their own resilience and collaborative spirit.

The notion began with Chesapeake Shakespeare Company producing executive director Lesley Malin, who initially wanted to stage all 10 plays with her company. That idea soon developed into asking other theatres, from members of Baltimore Small Stage Coalition to large LORT companies, to be involved in the citywide celebration. Malin also received the blessing of Wilson’s widow, Constanza Romero.

“It came out of the pandemic, and the focus on trying to expand what we consider a classic,” Malin explained. “We believe August Wilson’s plays are on the same level as Shakespeare…Wilson has a way of delving into the pain and celebrating the achievement of the Black experience at the same time.”

This isn’t the first full Wilson cycle. Over time, Chicago’s Goodman Theatre became the first theatre to produce all 10, and comprehensive staged readings took place at the Kennedy Center in 2008 and at New York City’s Greene Space in 2014. Another theatre that has completed the cycle is Baltimore Center Stage, which has produced all of Wilson’s work, some more than once, according to artistic director Stevie Walker-Webb. August Wilson Society VP and conference planner Khalid Long, the project’s dramaturg, and Malin both confirmed that this citywide celebration is the first such project mounted by a collective of multiple organizations.

The celebration started last April with Arena Players, with Gem of the Ocean. Chesapeake Shakes’s production of Joe Turner’s Come and Gone is next, Sept. 20-Oct. 13, followed by Fences in 2025. Also taking part are ArtsCentric, with Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom in 2025, Everyman Theatre (The Piano Lesson, 2025), Spotlighters Theatre (Seven Guitars, 2025-26), The Angelwing Project (Two Trains Running, 2026), Fell’s Point Corner Theatre (Jitney, 2026-27), Baltimore Center Stage (King Hedley II, 2026-27) and Noah Silas Studios/Theater Project (Radio Golf, 2026-27).

Malin and Long drew comparisons between Baltimore and Wilson’s hometown and frequent setting, Pittsburgh. Both Rust Belt cities have thriving, majority-Black communities, and Wilson wrote about and for Black people.

“There are history lessons opening up for us, their daily practice in the midst of these lives,” said Long. “For Black communities, D.C. used to be the mecca; Baltimore has its own central location. It’s very similar to Pittsburgh and Philadelphia, with the Great Migration from South to the North. It’s best to think about it in migratory patterns. The culture of cities might be different, but they are all connected via the Great Migration.”

Donald Owens, artistic director of Arena Players and director of its staging of Gem of the Ocean, had planned to stage it before the festival was announced, as part of Arena’s 70th anniversary season. When Malin called him and discovered the happy coincidence that Gem was already slated for Arena, and asked if Arena would kick off the project with their production, he said he took it “as an honor, but an honor I was going to do anyway.”

As Arena is the oldest continuously operating African American community theatre, Owens thought it was only fitting that they should kick off the celebration, and to do it with the first one in the series chronologically (Gem is set in 1904, and each of the 10 plays takes place in a different decade of the 20th century). “To see them in order, you understand the journey,” he said. “You can see them individually, but you don’t always know what they’re talking about.”

Gem of the Ocean, being closest to the historical institution of chattel slavery, deals directly with the memory of the Middle Passage in a memorable sequence envisioning a transatlantic City of Bones. As Owens put it, “This whole thing has been a trip we had not purchased a ticket for.”

Chesapeake Shakes’s Joe Turner’s Come and Gone, set in 1911, continues the cycle, in a first for the classics-focused company.

“Because it’s more of a period piece, it seemed to fit with us, and I wanted to have something early on,” said Malin. “I was knocked out by the story of this makeshift community coming together to support this truly broken man and help him find himself again.”

The community around the production, directed by KenYatta Rogers, has also opened many new possibilities for the company.

“So many actors walked in our door who’d never walked in our door before,” Malin said. Among them were young women in the company’s Black classical acting ensemble, company members, a lead actor who recently moved from Philadelphia, and Jefferson A. Russell, a resident company member with Everyman Theatre. All of this new blood has the company “excited about those cross synergies.”

Everyman associate artistic director and company member Tuyết Thị Phạm isn’t surprised to see Russell’s involvement. “He’s a Baltimore staple,” she noted. “He was a police officer in this town. For him, for many artists, especially Black artists in Baltimore, this is very meaningful.”

For her part, Phạm calls producing Wilson’s second Pulitzer winner, The Piano Lesson, at Everyman “the grandest opportunity. He’s just one of the titans—one of those writers that turns back the layers of what it means to be human. He’s one of the few theatre artists that if you say his name, you can get a whole lot of people to consent. I think it organically came together: big, little, medium-sized theatres, all going, ‘Yeah, we’ll shift our schedule for this man.’”

Phạm said that in her year and a half of being at Everyman, there has been “pining” to do Wilson. “What better time than the present, if the celebration is going on?” she said. “I sense that everyone was thrilled to be part of it. There was such a swell of possibility and joy around it, and where it sits now, it’s a giant river of possibilities.”

Phạm continued, “If we’re going to do August, we’re going to do it big. I think it’s one of his biggest plays in terms of cast size, in terms of scope, the scale of the mythology around it, and the supernatural elements. It’s one of the few plays that does all of that in his canon. It’s my favorite in the Century Cycle; there’s something about an object that so deeply represents family, if you are from a culture that has heirlooms and symbols that start to become larger than life and mean so much more than their monetary value.”

For its part, Baltimore Center Stage is taking on a later work, King Hedley II. Walker-Webb immediately knew he wanted to do this lesser-programmed play. He believes this project will resonate anew in the shadow of what he hopes is the nation’s first Black and South Asian woman president.

“Wilson looks at the plight, joy, triumphs, and travails of Black life in America,” Walker-Webb said. “What does it mean to look at a cycle that expands all these years, multiple generations, in a time when conversations around Kamala being president shakes and shifts all of us as American citizens? What would characters stuck in the windows of time feel about this? When you do this right and do it well, you get to hold up a mirror of society and measure the distance we’ve traveled. It’s a beautiful way to measure our progress as a people and as a nation, and to have that conversation over a period of years.”

According to Charisse Nichols, director of engagement at the Baltimore nonprofit The Leadership, who worked at BCS during the 1999 season, then-artistic director Irene Lewis had a close relationship with Wilson and with Marion McClinton, his confidant and director of choice at the time. Nichols recalled a moment from Jitney’s final dress rehearsal at BCS when the son, Booster, waits “for what feels like two minutes” to decide to answer the ringing phone and say, “Jitney.”

“Having lost my father seven years prior, that moment brought a flood of emotions, and I sat there weeping for about a minute before the lights went up,” Nichols recalled. “As I tried to pull myself together, I felt a hand on my shoulder that stayed there for a while. It was August. We said nothing but looked at each other. To say I was breathless is an understatement. The only thing that topped that moment was being able to meet the poet Maya Angelou at his opening night party. As the kids say, it’s a core memory.”

This project is still evolving. By this summer, all 10 companies were on board and plays were selected. Between productions and seasons, Long and Malin are also committed to four major events throughout the celebration to honor Wilson’s legacy and the ways it is reflected in Baltimore, for continued conversation and momentum.

Chesapeake Shakes will offer a day-long “Teaching August Wilson” workshop to provide Baltimore-area educators a rich variety of approaches to introducing students to Wilson’s work. Future events are not yet solidified but may include curated panels with Wilson scholars, historic perspectives on the Great Migration, or storytelling workshops.

“I hope people go off and learn more, but also that people return to theatres in the coming years, not just to go to shows, but go to their community events as well,” Long said.

Common hopes for the celebration are for Baltimore to be seen as a player in the American theatre, as well as for local sustainability and longevity.

“There are many places where you can experience the finest theatre, and you don’t have to go far,” Phạm said. “You don’t have to go to New York, you don’t have to go to Chicago. That’s my hope: that people see this underappreciated groundswell of artists emerging out of Baltimore.”

They also hope local artists get opportunities and young audiences receive education, especially with Chesapeake Shakes and BCS’s student matinee programs, which reach thousands of students yearly. Participating organizations plan to support each other throughout the cycle, from scene shop borrowings to Malin’s idea of passport books—she said she hopes theatregoers will have 10 stickers for all 10 plays by the end.

“I believe in theatre as a way to bring people together,” she said. “One of the things I have always regretted about the Baltimore theatre community is that it’s very siloed, and that there is no opportunity…to work together. Honoring this great playwright and his work here felt like the right thing to do to bring the theatre community together, so all of us could be serving that larger Baltimore community.”

Together they’re proving theatres don’t have to compete, and that theatre is a central part of civic life.

“We all jumped to say yes because we want to lock arms and demonstrate what collaboration can be,” Walker-Webb said. “I can’t think of anyone better than Wilson to help us demonstrate it. We all deep inside think a story can save the world, a play can push a conversation forward. Now we’re having one big conversation rather than all these smaller conversations.”

Best of all, conversations have begun with people who’ve never seen Wilson’s work before.

“Some people came who were not familiar at all with August Wilson, and now we get to see them all,” Owens said. “We’re about to have a hot time in Baltimore.”